The science of the camp rations

“I can’t describe what it is to see these children lying about in a state of collapse – it is just exactly like faded flowers thrown away. And one hates to stand and look on at such misery and be able to do almost nothing,” Emily Hobhouse wrote in 1901 after her first visit to the Bloemfontein concentration camp.

Although her words sounded desperate at the time, she eventually managed to improve the conditions in the camps. But it took perseverance and determination.

Prof. Celeste Naudé, Dietitian and Chief Researcher, Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Stellenbosch University. Naudé conducted an analysis of the Story of Emily, focusing on her expertise in nutrition. She helped us with one of the projections comparing the rations one can see in the War Rooms.

It was Emily who collected the official information from the authorities about the rations people received in the concentration camps of the Anglo-Boer War. Today, the information she collected in January 1901, which was also published in her report and her book The Brunt of the War and Where it Fell in 1902, is the basis of what people received.

As a means of punishment and to discourage the Boers from continuing the war, there was discrimination in the rations. Families of men who were still fighting were called “undesirables”, and they received less food, including the children. The rest were referred to as “refugees” by the British military authorities. They were, however, not free to leave.

“Refugees” - adults

Mealie-meal or samp/potatoes/flour/rice: 1 lb per day

Meat: ¾ lb per day

Coffee: 1 oz per day

Sugar: 2 oz per day

Salt: ½ oz per day

“Undesirables” - adults

Mealie-meal (or samp/potatoes/flour/rice): ¾ lb per day

Meat: 1 lb, twice a week

Coffee: 1 oz per day

Sugar: 2 oz per day

Salt: ½ oz per day

Children under 6 years (“Refugees”)

Flour or mealie-meal: ½ lb per day

Meat: ½ lb per day

Evaporated milk: ¼ tin per day

Sugar: 1 oz per day

Salt: ½ oz per day

Children under 6 years (“Undesirables”)

Mealie-meal: ½ lb per day

Meat: ½ lb twice a week

Evaporated milk: ¼ tin per day

Sugar: 1 oz per day

Salt: ½ oz per day

Would one live on this amount of food?

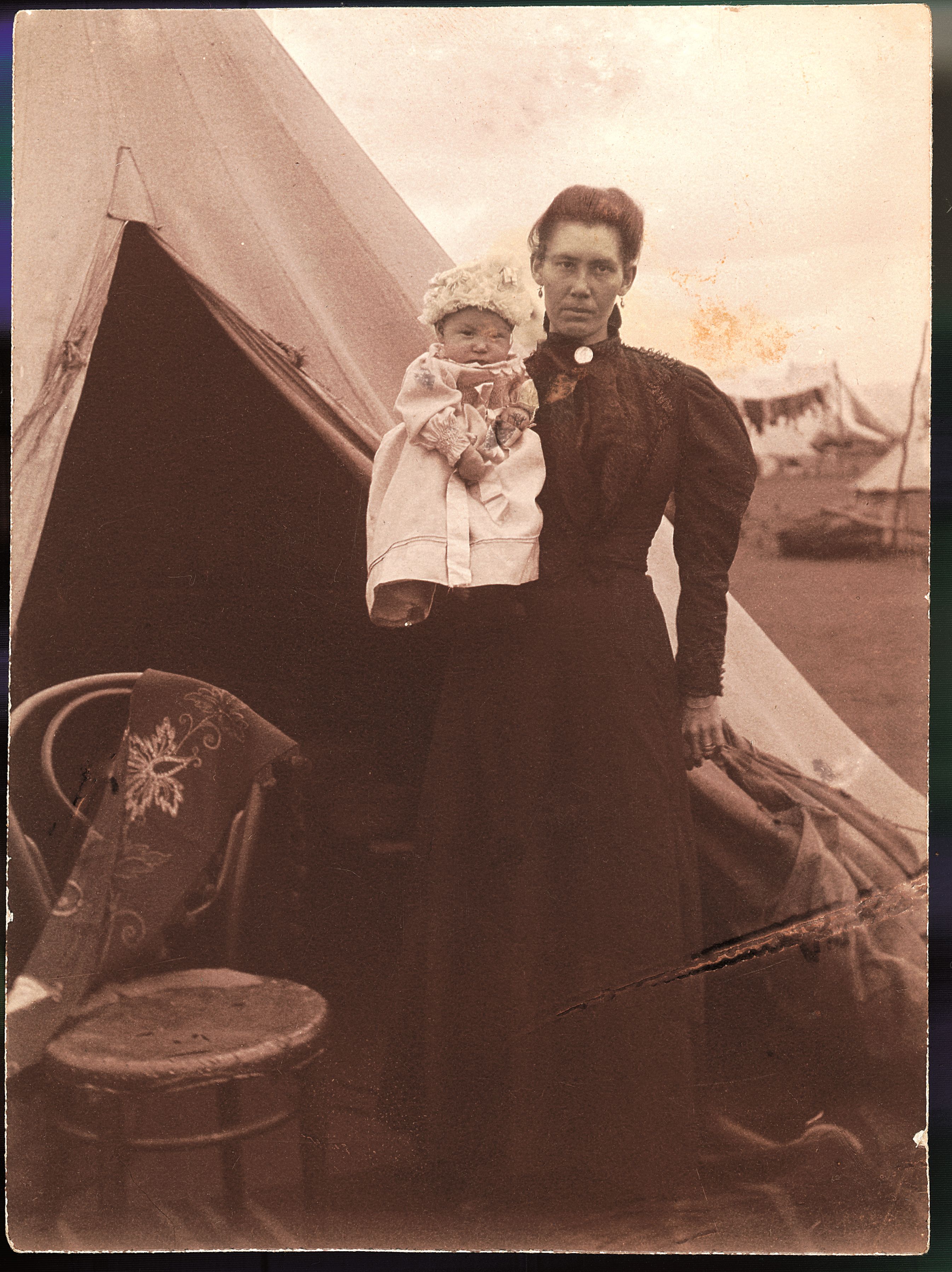

The Story of Emily asked Naudé to examine the rations scientifically. Many women had babies, and they would have been breastfeeding, so that is the example we chose.

What are the nutritional and energy needs of an active, 30-year-old woman who is breastfeeding? This menu is an example of 11,310 kJ (2703 calories).

Breakfast

1 cup muesli

1 small plain yoghurt

1 slice of toast with cheese and marmalade

Lunch

1 egg mayo sandwich

1 small Greek salad

1 medium bowl of fruit salad

Dinner

1 regular fish in batter

1 regular potato chips

2 serving spoons of carrots

2 serving spoons of peas

1 medium square apple crumble

The daily energy needs of an active 30-year-old woman of average height (1.63 m) and weight (60 kg) range from about 9900 kJ (2366 calories) for an active lifestyle to 11300 kJ (2703 calories) for a very active lifestyle. If she is lactating a young infant (< 6 months of age), this woman needs about 11300 kJ (2703 calories) to 12600 kJ (3011.4 calories) per day if she is very active.

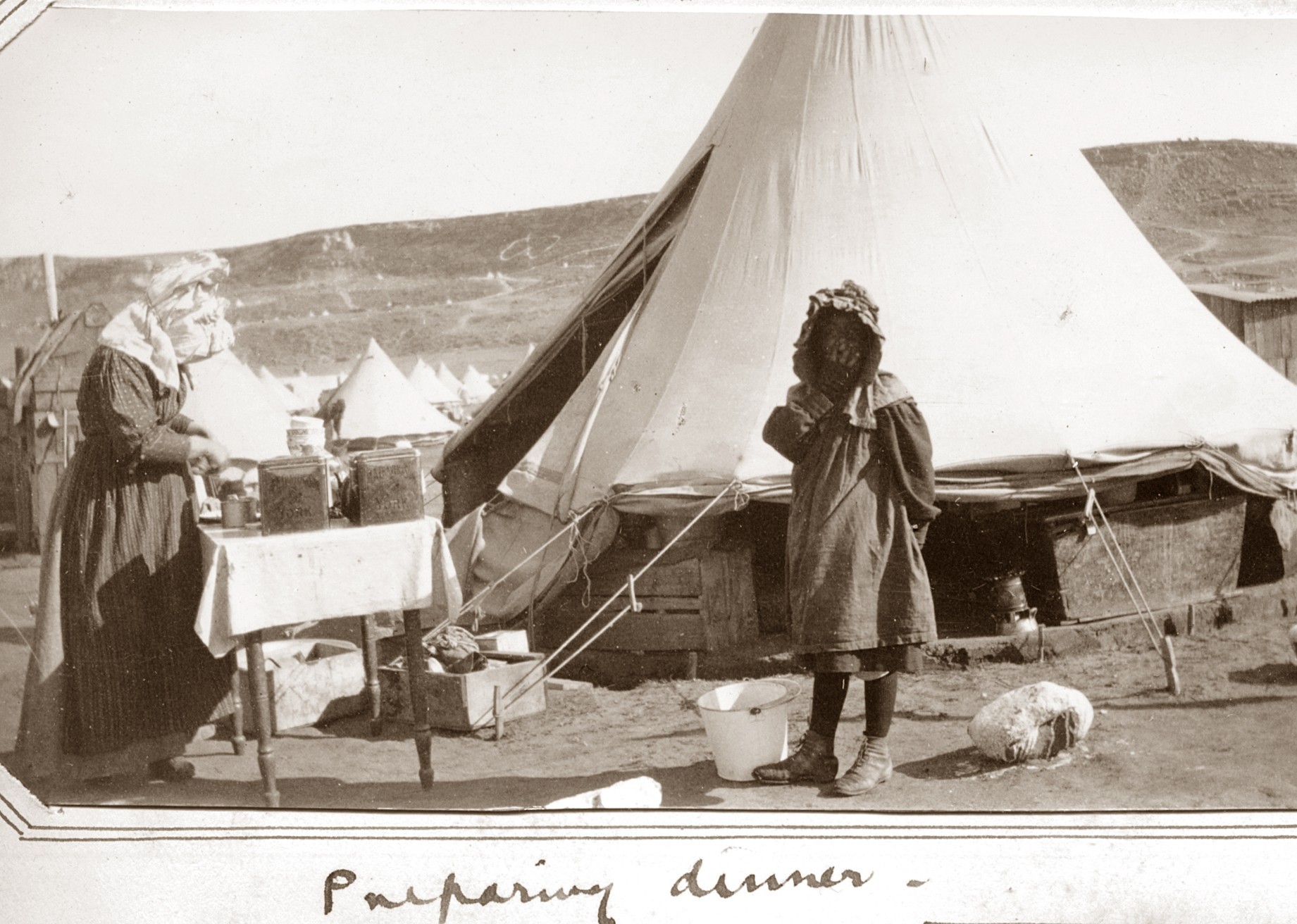

When compared to what the women received in the camp, it is not sufficient at all. Depending on the kind of carbohydrates they received.

It is indicated that they received either mealie-meal or samp (a staple food from maize that guests can taste at the Restaurant at the Story of Emily), flour, rice, or potatoes. All these differ in energy value depending on the amount given, along with the meat, a bit of sugar, salt, and coffee.

If given flour, the energy provided was 9,331 kJ (2,230 calories), maize meal 8,405 kJ (2.008.4 calories), samp 8,223 kJ (1,965.3 calories), rice 7,052 kJ (1685.4 calories) and potatoes 3,706 kJ (885.7 calories).

The energy provided by the rations for “refugees” would provide less energy than a 30-year-old woman of average height and weight, who is breastfeedig needs per day to stay healthy. She would therefore lose weight over time.

For the “undesirables”, this deficit would be even greater. The lack of energy over weeks and months would lead to dramatic weight loss and eventually emaciation from starvation, particularly in the “ undesirables”, where weight loss and deterioration would be faster and worse. These women would experience intense hunger, particularly if they were consuming energy only at the lower end of the range, Naudé’s analysis showed.

“The daily camp ration diet for adult women is deficient in many vitamins and minerals and would fail to meet these women’s needs for most of them, particularly key nutrients such as calcium, iron, iodine, folate, vitamin C, and vitamin A. This is mostly due to a lack of fruit and vegetables in the diet and a limited variety of foods.

“This diet would result in nutritional deficiencies over time, leading to a breakdown in the functioning of all systems in her body, including the immune, digestive, nervous, muscular, circulatory, and skeletal systems. The poorly functioning systems would manifest in nutrient deficiency conditions and symptoms such as scurvy, anaemia, night blindness, bleeding, muscle weakness, neurologic conditions and skin conditions. A weakened immune system would make her highly susceptible to infections, which would be made considerably worse by a lack of sanitation and exposure,” Naudé wrote.

The needs of the children

Naudé studied the information for both groups of children and compared the energy needs per day for a 3-year-old of average height: boy: 96 cm, girl: 95 cm, and weight: boy: 14.4 kg, girl: 13.8 kg. Their daily needs are about 6000 kJ (1434 calories).

Sometimes the children received tinned evaporated milk, other times condensed milk. But here we share the analysis of the more common evaporated milk, if it was given, which was not always the case.

The energy provided by the rations for children “refugees” would be less than what a child needs to stay healthy and grow to their full potential, even with the milk.

Depending on the type of carbohydrates given, the energy was between 2684 kJ and 5496 kJ(641.4 and 1313.5 calories) for the “refugees” and far less for the “undesirable” children.

These children would experience intense hunger, particularly if they were only consuming the amount of energy towards the lower end of the range, Naudé wrote in her report.

She continued: “The daily camp ration diet for the children is highly deficient in many vitamins and minerals and would fail to meet their needs for most of these, particularly for key nutrients such as calcium, iron, iodine, folate, vitamin C and vitamin A. This is mostly due to a lack of fruit and vegetables in the diet and a limited variety of foods.

“A child with this diet would develop nutritional deficiencies over time. These would cause a breakdown in the functioning of all systems in the child’s body, such as the immune, digestive, nervous, muscular, circulatory and skeletal systems. The poorly functioning systems would manifest in nutrient deficiency conditions and symptoms such as scurvy, anaemia, night blindness, bleeding, muscle weakness, neurologic conditions and skin conditions.

“A weakened immunity from the poor diet would make the child highly susceptible to infections, which would be made considerably worse by lack of sanitation and exposure. This would result in a vicious cycle because malnutrition makes a person more susceptible to infection, and infection also contributes to malnutrition.”

At the time diseases that were prevalent in the camps included measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever, bronchitis, diarrhoea in babies, diphtheria and pneumonia.

Emily wrote: “ They accused me of talking politics, whereas we could only talk of sickness and death, they objected to ‘shewing sympathy’ but that was needed in every act and word. It was all kept very quiet; after a while the corpses were carried away at dawn, and instead of passing through the town approached the cemetery another way – many were buried in one grave.”

After the conditions improved – largely due to her campaign under the auspices of her South African Women and Children Distress Fund, at the end of 1901 and the beginning of 1902, she kept track, and these improved rations were also published by Emily.

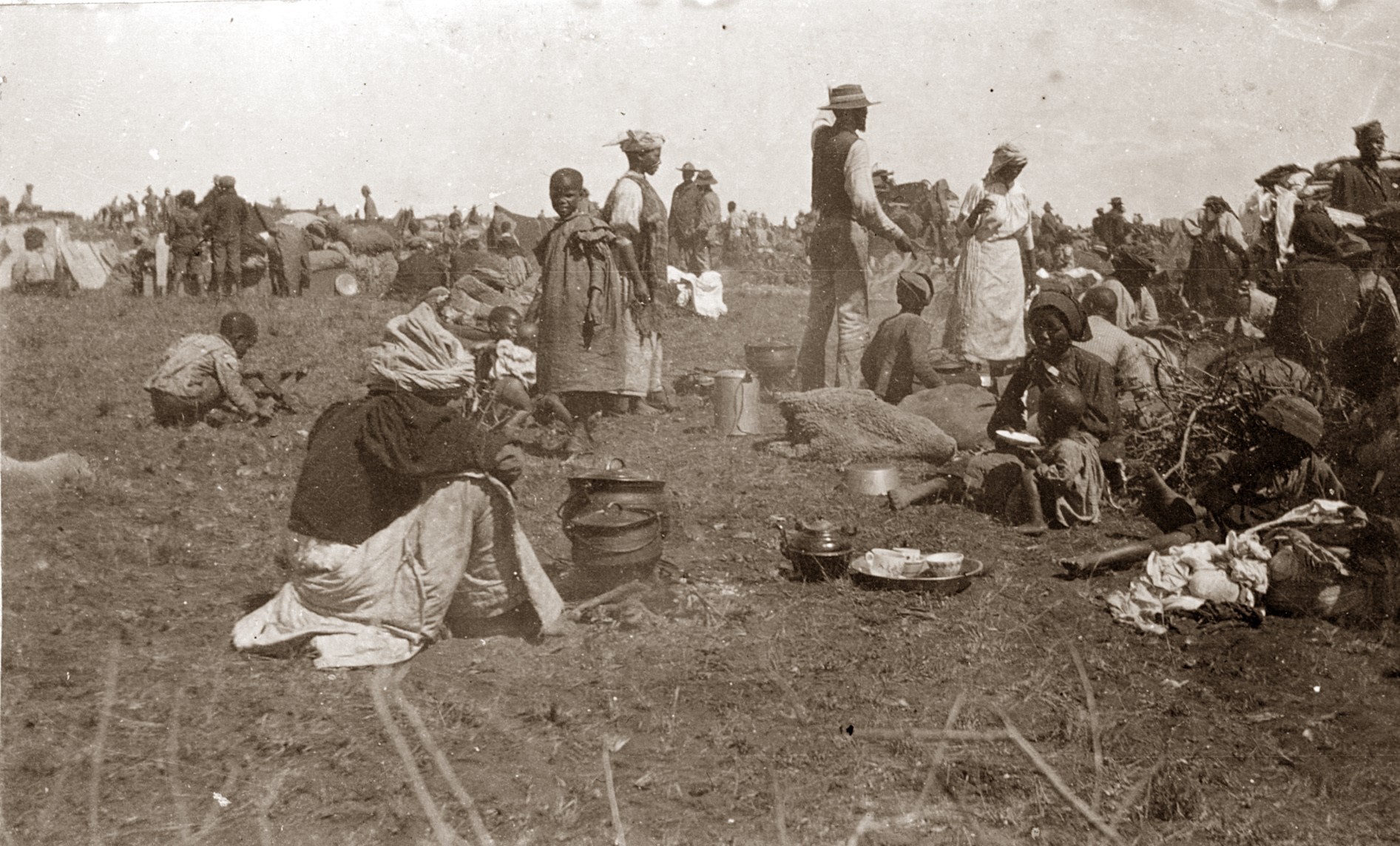

The black people

Black people, women, children and men were also forced into concentration camps (we will share another blog about their experiences in the near future). There were individual black girls and or women who were interred with the white women and children, but they were the minority.

It is important to know that the camps for black people fell under a British military-operated department called the Native Refugee Department. These evolved from initial concentration camps to forced labour camps, as shown by the research of Dr Gath Garth Benneyworth and others.

The men who were swept up from the Boer farms and surrounding areas were compelled to work for the British military and also on the gold, diamond and coal mines. The British government, therefore, introduced the “ no work, no food policy”, which was administered by the Native Refugee Department.

This resulted in an increase in starvation, diseases and malnutrition in the camps for black people. Benneyworth writes that not only is the word “ refugees” a misnomer, but black people were harnessed through this no-work, no-food policy as a resource to underwrite the total war strategy. Men were coerced into working for the military and for the mines, and women and children were used as agricultural labourers for the British Army.

The meagre rations noted for those aged 12 or older:

1 and ½ lb of either mealies, corn (daily)

¼ oz salt (daily)

1 lb of fresh/tinned meat (weekly)

½ oz coffee

3 oz sugar

Under 12 years

1 lb either mealies/corn (daily)

¼ oz salt

¾ lb of fresh/tinned meat (weekly)

½ oz coffee (weekly)

2 oz of sugar (weekly)

These rations were even less than those of the other camps. And it is clear that it was extremely inadequate. (The book by Benneyworth was published in 2025, after the analysis was done by Naudé.) However, archival information about the camps for black people remains fragmentary.

Emily wrote during her travels in 1901 about war: “You can no longer be an individual, you are one of a herd – and that herd preserves itself by the reversal of the principle of virtue. Untruth, lies, hatred, inhumanity, destructiveness, spying, treachery, meanness innumerable, suspicion, contempt, unfair dealing, illegality of every kind flourish and become as it were the ‘virtues of war’. The atmosphere thus created is a moral miasma.”

Sources:

1. Prof. Celeste Naudé, Dietitian and Chief Researcher, Centre for Evidence-Based Healthcare, Stellenbosch University. Report for The Story of Emily

- Nutritional analyses conducted according to the South African Food Data System (SAFOODS) using Foodfinder III: Dietary analysis software, South African Medical Research Council, 2002

- Holland R, Loveday D, Ferguson K. How much meat to expect from a beef carcass. University of Tennessee, Institute of Agriculture, United States Department of Agriculture https://extension.tennessee.edu/publications/documents/pb1822.pdf.

- Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs), Institute of Medicine, United States Department of Agriculture.

- Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs), Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine (IOM)

2. The Brunt of the War, 1902, Emily Hobhouse.

3. Feminist, Pacifist, Traitor? 2018, Elsabé Brits

4. Work or Starve, Black Concentration Camps & Forced Labour Camps in South Africa, 1901-1902, Garth Benneyworth.